surrender to the terrible

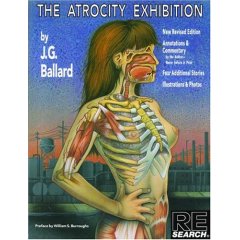

I once applied to write a monograph on J.G. Ballard, and while I'm glad I wasn't saddled with that project before I had even completed my dissertation, I still have a soft spot in my heart for him in all his perverse complexity. John Foxx of Ultravox does, too.

I once applied to write a monograph on J.G. Ballard, and while I'm glad I wasn't saddled with that project before I had even completed my dissertation, I still have a soft spot in my heart for him in all his perverse complexity. John Foxx of Ultravox does, too.

From the late 70s to the early 80s, it seemed that most “post-punk” artists were happy to claim Ballard as an influence: Numan, Siouxsie, Ian Curtis, Cabaret Voltaire, yourself… Why did Ballard have resonance for such a particular group of musicians back then?

I think some of this may have been an attraction to the new modes of physical and intellectual violence on offer and to the uncompromising outer edge stance. This attraction naturally alters as the ‘mode of the music’ changes. Many other writers have since begun to colonise what JGB established, and elaborated that grammar to deal with new technological events, but it’s still essentially the same stance.

He was the first radical and relevant novelist of this technological age in Britain. You had Burroughs and Philip K Dick in America but they were connected to the beat movement, using drugs as a lens, reflecting an American landscape. I always enjoyed JGB’s Englishness, living in a middle-class suburb writing about a new landscape we’d only just come to live in – more akin to McLuhan’s academic/romantic take on the unrecognised present.

I think what Ballard maps out so well is that moment of surrender to the terrible. A total, inevitable, final embrace. After Hiroshima we really had no choice. It was impossible to pretend that the world would ever be the same again. We all sleep there every night, now. Ballard blueprinted all that like no one else I’ve ever read.